By Yogaratna

I want to focus on two ways we can respond with positive emotion to the overall situation (of climate change, biodiversity loss, authoritarianism in the world. Ways of responding with positive emotion which can be cultivated. The two ways are to do with playfulness or humour (or what I’m labelling ‘carnival’) — and faith.

Why am I talking about ‘carnival’? I think it has a very useful range of meanings and associations. According to the dictionary: an annual festival, typically during the week before Lent in Roman Catholic countries (which happens to be now), involving processions, music, dancing, and the use of masquerade or dressing up. More generally it can be an exciting or riotous mixture of elements. Historically carnival sometimes involved playful inversion of hierarchy: servants becoming masters.

Carnival and theatre have been influential in how protest is done, especially in the last twenty years or so. At Seattle in 1999 (protests against global trade agreements) the police were sometimes heavy-handed in their response to peaceful speaking out. The police had apparently been trained in the expectation that they would be facing violence. On some occasions they really didn’t know how to respond — when, for example, all the protestors suddenly sat down. And there were also ‘Pink Blocs’ of protestors dressed in tutus armed with feather dusters for tickling the police.

This is an example of something I think is very important — an ethically positive, playful or carnivalesque response to what may seem overwhelmingly difficult situations, and abuses of power. Mikhail Bakhtin once wrote: ‘laughter must liberate the happy truth of the world from the veils of gloomy lies spun by the seriousness of fear, suffering and violence’.

Laughter can be a very strong and deep energy — and of course not all laughter is good laughter. Laughter can be very unskilful, even abusive. But it can be highly skilful (the laughter of enlightenment in the Vajrassatva mantra for example ‘ha ha ha ha ho’). It’s important why we’re laughing, and how.

But play, carnival, laughter can be ethically positive — and maybe loosen us up if our worldviews have got a bit rigid or polarised. I’m going to use Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita as an extended example of what I mean. It’s mainly set some time in the 1930s, and tells the story of what happens when the devil (and his very mischievous cat) visit the rigidly atheistic Soviet Union. It’s a very knowing and witty parody of Soviet society at that time: wildly carnivalesque, full of magic, religion, and the romantic. The satire is against repression of freedom of thought and of speech — against an authoritarian society’s dismissing of the imagination, of religion itself and the mythic dimension. And yet nobody seems responsible for the way things are — the characters in the story don’t come across as particularly bad. Even the devil character doesn’t actually seem bad — far more mischievous and subversive, maybe a symbol of a society’s repressed energy. I’d say the novel itself ultimately celebrates romantic love and people caring for each other — and the energy of the human imagination.

So I think Bulgakov’s novel was written to some extent against Stalin’s Soviet Union — the authoritarianism, the millions of State-sanctioned murders, the violent repression of free speech and different points of view. And it was written against fear itself. It is deeply serious, but also great fun, a celebration of some of the wilder human energies.

Hard to know what would have happened if Bulgakov had tried to publish this novel (as he intended), since he died of natural causes (in 1940) as he was finishing it. This was the time when writing a satirical poem about Stalin could get you executed — which is pretty much what seems to have happened to the poet Osip Mandelshtam. But The Master and Margerita lived well beyond its creator – secretly passed from hand to hand, it was known and loved by many thousands of Russians decades before it was finally published in the Soviet Union in 1968.

When faced with what can seem an overwhelmingly difficult situation, all the positive human qualities matter. But perhaps this satirical energy and wild, magical but ethically positive vision are particularly valuable in cutting through what might be a repressed, cowed, fearful state of mind. Skilful laughter is so opposite to cowed and fearful.

In our own time, right now, the far-right seems to me scarily influential and close to dominance in the USA and Europe, and we may well be on the unstoppable ride of runaway climate change. In some ways, things are looking even grimmer than in Bulgakov’s lifetime. Hopefully, things politically won’t go too far in that direction. On the other hand it seems worth considering that one day we might need to think in terms of resistance rather than outright opposition – of keeping positive vision alive in covert forms, like bulbs in the ground surviving winter. Which is what Bulgakov’s novel was part of back in the 1930s. Maybe even our Buddhist practice itself will need to be more covert and under the radar.

If we’re going to face the big picture, we’re going to need inspiration and emotional sustenance — to keep our souls and spirits alive. Obviously, we can find inspiration in our friendships and relationships, in our practising the Dharma, in the sangha. But it might be helpful to deliberately cultivate more symbolic, non-rational sources of inspiration (aka the mythic context) – perhaps there are parts of us which can only be reached this way. Maybe all great poetry, art, music by tapping into the mythic, has something of this liberating and inspiring function. By the way I’m sure we are all already doing this, I’m just suggesting that it’s really important at a deep level for long-term emotional resilience. So how might we do this in practice? We all probably have our own ways. We could maybe try something we haven’t done before, which might be a clowning workshop, or action theatre (a very in-the-moment, embodied and self-aware form of improvisation where you come up with stories and maybe respond to other people as they improvise). We can listen to and be inspired by carnival (in the sense I’ve been evoking) as it manifests in the arts: books, films, dance etc.

So that’s a bit about carnival. What about faith?

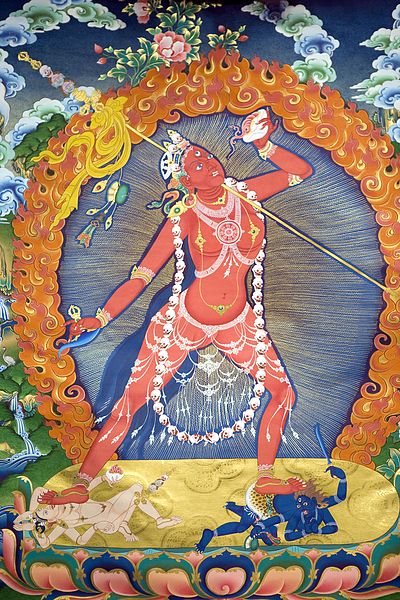

In fact the Buddhist tradition does have its own wild and playful sides. One of many examples (from the Tibetan Vajrayana in this case) is Vajrayogini. She’s a sort of archetypal Enlightened deity figure. She has the form of a beautiful young woman, naked apart from a few symbolic bone implements. Her skin is red, the colour of unconditional, universal loving-kindness.

She’s ecstatic and free, dancing in the sheer void of ultimate reality – sometimes she’s represented as dancing on (or trampling) bodies representing greed, hatred and delusion.

She takes no prisoners. If we dare to dance with her (perhaps by engaging in years of spiritual practice) she will destroy us utterly – and make us into something far beyond what we were.

Vajrayogini might sound a bit much! Not everyone’s cup of tea maybe. But meditating on Vajrayogini is just one example of a Buddhist faith practice — which can be more of a slow burn, or long fuse. Such an important and deep energy. Our heart-response to our ideals of love and compassion. During meditation I sometimes visualise the Buddha, with golden light radiating from his heart to mine. Very simple and undramatic. But it works — I feel it physically, and in my depths emotionally. If my values or interests have been maybe getting subtly superficial, materialistic, self-centered — then faith practices like this one help remind me, reconnect me with what I really care about at a deep level. And that can feel like a deep relief, and release of positive energy.

There’s the saying that faith can move mountains — and it’s true. It does. It’s what motivated Martin Luther King, the suffragettes — so many heroic people who changed the world for the better. Maybe we aren’t heroic, it’s ok not to be a hero! tho I suspect many of us are in reality more heroic than we think we are. But whatever or whoever we are or think we are — we can all play, we can all harness that deep wild playful energy. We can all draw on deep skilful inspiration, wild energies, and we can all cultivate faith.

Thank you thank you Yogaratna! Very briefly here I’ll say (I intend to come back to your piece soon …) you bring together these vital areas/elements. Show compellingly how they are complementary and mutually nourishing. My/our ability to be well & flourish seems to me crucial while we act to bring change, put ourselves on the line, under various, and sometimes extreme, internal & external pressures and limitations, restrictions, possible threats and anxieties. And there’s still that every day business of getting by, meeting obligations, ‘paying the bills’, hassle and all … What you offer I feel invites me towards the beauty and humanity of joy/humour/release and the complementary experience of awe/purification/potency. Both have the deep Tastes of Freedom that I yearn for. Thank you very much for these insights, & terrific encouragement. Sasanajyoti

You’re very welcome Sasanajyoti, and thank you very much for your appreciation.

Good for me to revisit this area! It’s very much a practice isn’t it?

All the best